Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Last month I wrote about why it can be so hard for human beings to make change. Even if we are deeply unhappy with some aspects of our lives, we often resist making change and stumble and backslide when we do try to change. This month, I want to look more closely at some effective strategies for making major life changes. The key to many life changes is changing our behaviors, and changing behaviors is about changing habits.

A habit is a behavior that has been repeated enough to become automatic. In his book Atomic Habits, writer James C. Clear synthesizes much of the research on habits—on building good ones and breaking bad ones. He argues that “habits are the compound interest of self improvement.” In other words, small changes really add up over time. He says, “Changes that seem small and unimportant at first will compound into remarkable results if you’re willing to stick with them for years. . . . With the same habits, you’ll end up with the same results. But with better habits, anything is possible.”[i]

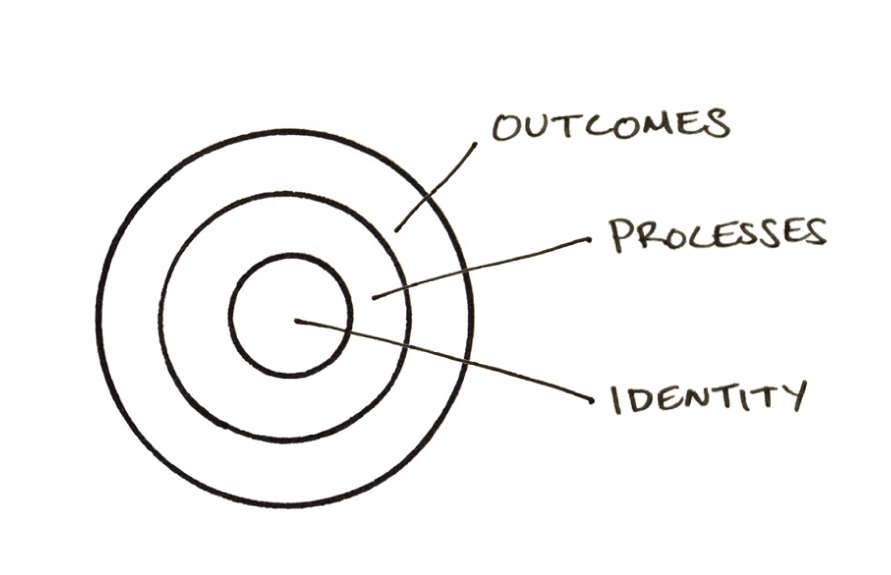

Clear challenges the notion that change is about setting lofty goals for yourself. He notes that “achieving a goal only changes your life for the moment.” To make long-term change in our lives, he says that we need to understand the nature of change. Behavior change has three layers.[ii] The first layer is changing outcomes. This is changing the results. Changing outcomes might involve losing weight, changing a job, or embarking on a new career. This is the layer of behavior change associated with goals.

Image source: https://jamesclear.com/identity-votes

The second layer of behavior change is changing your process. The focus here is on implementing new routines and systems that can support the outcomes you want, like developing a new exercise routine or devising a system of organizing your home to reduce clutter. Better processes or systems support long-term change.

And finally, the deepest layer of behavior change is about changing your identity. This is about shifting your worldview and your mindsets as well as your judgments about yourself and others.

Clear summarizes it this way: “Outcomes are about what you get. Processes are about what you do. Identity is about what you believe.”[iii]

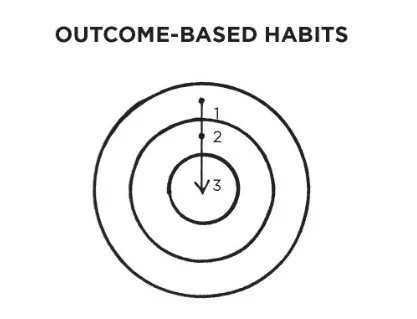

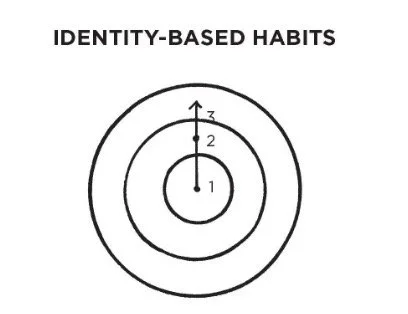

Clear says that the direction of change matters. He maintains the least effective way to make change is to begin by focusing on the outcomes. (see diagram). The more effective approach is to begin by focusing on identity. “True behavior change is identity change,” Clear says. In other words, by focusing on who we want to become, we can build and sustain habits to support long-term change.

Image Source: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/articles/atomic-habits-excerpt/

For example, an outcome-based approach to change might be to say, “I want to read 50 books this year.” You might achieve this goal, but the focus is really on the outcome—on checking off that list of 50 books. With this goal, you might not change your fundamental reading behavior for the long term. What if your goal instead was “to become a reader”? Or if your goal was not to learn to play the guitar but to be a musician? Or if your goal was to become a healthier person instead of to lose 30 pounds? Instead of saying “I want to write a book,” how about “I want to be a writer.” As you begin to drill down into what it means to be a reader, a musician, a healthy person, and a writer, the types of changes you need to make to have the life you want will come into clearer focus.

Image source: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/articles/atomic-habits-excerpt/

Research shows that our behaviors are usually a reflection of identity. If you tell yourself “I’m terrible with technology,” you’ll probably resist adopting new technology. If you say, “I’m not a morning person,” you’ll resist changing your routine to make space for morning exercise or meditation. As Clear puts it, “Habits are how you embody your identity.”[iv] If you can align your habits with your identity, you will be far more likely to sustain behavioral changes for the long term.

Clear says change is the simple two-step process of deciding the type of person you want to be and then proving yourself to be that person with small wins. Each new good habit teaches you to trust yourself and believe in yourself. It may be a simple process, but it’s not an easy one.

You can read Clear’s book (or find some great short articles on his website) to learn more about strategies for changing habits. But my focus here is on changing the things that aren’t working in your life. That kind of change requires us to keep our attention on identity. What kind of person do you want to be? How would that person behave? If you want to become that kind of person, what kinds of choices do you need to make?

[i] James C. Clear, Atomic Habits, (New York: Avery, 2018): 7.

[ii] Clear, 30

[iii] Clear, 30-31.

[iv] Clear, 36.